Diving Deep with Data: The Conservation Numbers Game

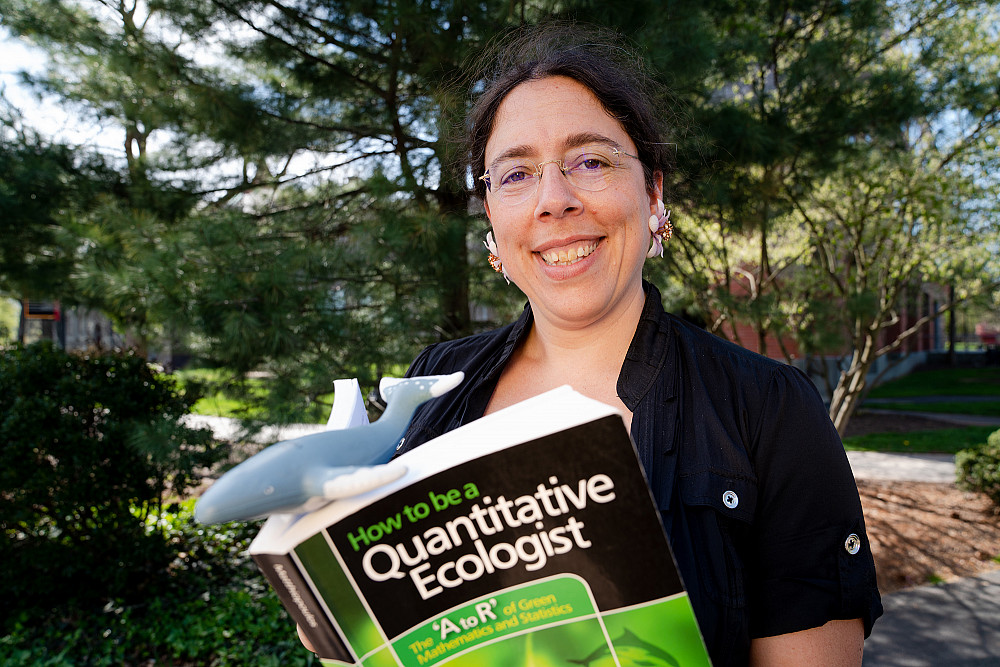

Ursinus data analyst Leslie New combines a love for math, animals, and the environment to help inform wildlife conservation strategies.

Leslie New couldn’t understand why she needed to study math. She had gone to college to study environmental science and natural resources, not calculus.

But in her senior year at Cornell University, when she walked into a class focused on wildlife population assessment and her professor, Evan Cooch, warned the students not to expect anything “warm and fuzzy,” it began to click. As she learned how math can be used to track a population’s birth and death rates and the growth or decline of a species, she realized that to understand how to care for animals, she needed to understand the data that described them.

“It was all math—linear algebra, calculus, straight-up arithmetic—and I ended up loving it,” said New, an assistant professor of statistics at Ursinus College.

Twenty years later, she has combined a passion for animals and the environment with a devotion to mathematical rigor to become a leading researcher in the field of statistical ecology, which models animal populations to inform wildlife conservation and management strategies. Her work has shed new light on the health and habits of eagles, whales, dolphins and more, bringing clarity to the murky waters in which marine mammals live.

New has been “totally transformative in our understanding of marine ecosystems,” Rob Harcourt, a professor of marine ecology at Macquarie University Marine Research Centre in Sydney, Australia, said.

Following her first class with Cooch, New dove deeper into courses he taught on estimating animal abundance and applying math to environmental conservation. After graduation, when she began working in wildlife rehabilitation and as an educator with the Philadelphia Zoo—with a stint as a pastry chef on the side—she realized that she kept seeking out ways to apply what she had learned in his classes. So, after going to night school to catch up on some of the math she had previously overlooked, she went to the University of St. Andrews in Scotland to earn a joint Ph.D. in statistics and biology.

In her work, New collaborates with ecologists and biologists who handle much of the field work that informs her models. She occasionally joins them, because knowing how data is collected plays a key role in analyzing it, but “as much as I like being outdoors,” she said, “I also like a comfortable bed and a hot shower at the end of the day.” Nonetheless, she sometimes finds herself standing in a Wyoming field taking notes about eagle flight patterns to mitigate the risk of their collision with wind turbines, or in a plane over Alaska watching whales travel along the sea floor. Most of her work, though, is done with the information collected on expeditions like these.

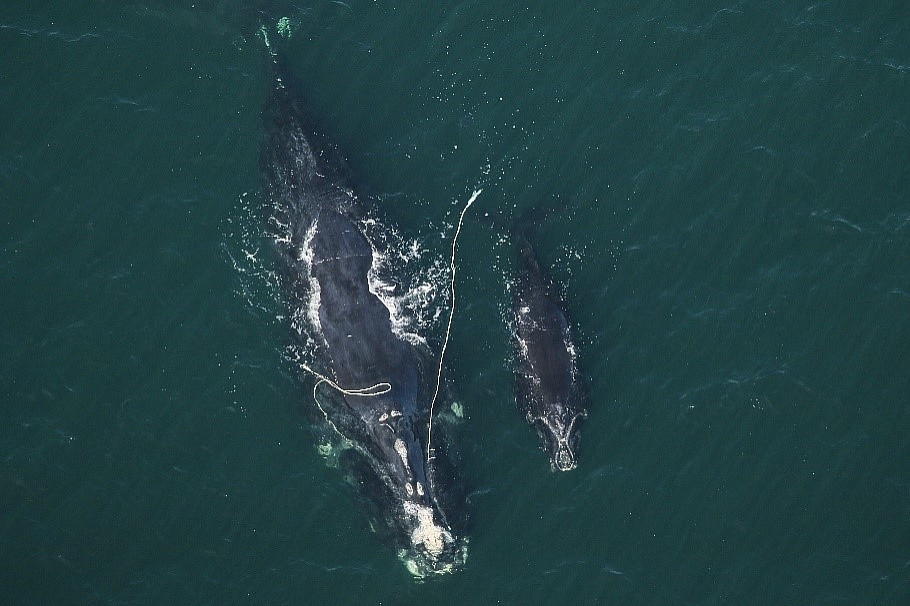

In many cases, data is extremely hard to come by, particularly for marine mammals that spend the vast majority of their time far beyond human sight. With nothing more than a few remote sensing tags placed on beaked whales and passive acoustic data, for example, New has developed models that can help scientists understand what wildlife populations need to survive and thrive—and how human activity, including pollution and environmental disruption, can alter a species’ course. Her research seeks to answer a complicated question: “How do we take this very specific information about a handful of individuals and generalize it to an entire population so we can make sure our actions as humans on this planet don’t wipe out other species?”

Through her work with colleagues at Macquarie University and elsewhere, New created a framework to anticipate the long-term, population-level impact of short-term disturbances to a species’ habitat, such as the installation of offshore wind turbines or an increase in shipping traffic. Harcourt, who has co-supervised three graduate students with New, says this work, known as the “population consequences of disturbance” framework, has allowed scientists to understand the measurable effects of small changes to an animal’s life history. A shift in a species’ environment could change feeding or mating habits, significantly altering a population’s trajectory even without the direct harm caused by potentially fatal incidents such as a ship strike or fishery entanglement.

When it comes to understanding animals’ behavioral patterns, “it’s not necessarily what you saw but what you didn’t see,” said Joanne Potts, director of The Analytical Edge Statistical Consulting. She and New overlapped in their time at St. Andrews’ Centre for Research into Ecological and Environmental Modelling and have since worked on multiple projects together, including two focused on expert elicitation—a method of collecting data from interviews with authorities on a subject, such as a specific whale population, when field data is insufficient or absent to create models.

Because the available data in statistical ecology is often sparse, New says it is more important to wield it effectively to influence conservation decisions. That means ensuring her methods aren’t biased or sensitive to assumption, so her collaborators have what they need to guide their research.

“Rather than sticking a square peg into a round hole,” she said, “I can help carve out the right-shaped hole.”

In the recent past, the field of ecology was largely defined by field naturalists who went into the wilderness and described what they saw. Statisticians like New—and the advanced models they employ—are leading the study of wildlife populations into a new era, Harcourt and Potts said.

“Ecology is only natural history if we don’t have the statistics, and natural history is the purview of the gentlemen of the 1800s,” Harcourt said. “We have to have rigorous statistical approaches. Ecology is all about understanding complex patterns, and you can only do that with good statistics.”

The ability to implement and understand complex models like those New creates “was just a pipe dream when I was young,” Harcourt said. Now, though, animal experts can detect important information in what might otherwise seem like biological noise. As all that knowledge adds up, the question hanging over the field of ecology is how to work with decision-makers in government and industry to balance the needs of mankind with those of the rest of the animal kingdom.

The bald eagle offers a window into that process. After decades of hunting, habitat loss and exposure to the harmful pesticide DDT, the bald eagle was listed as a threatened species in the 20th century, when the number of breeding pairs had dropped into the hundreds. But in 2007, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service delisted the species because its population had been restored to healthier levels. To ensure that progress continues, bald eagles are still a protected species, limiting any action that harms them.

New has worked with the Fish and Wildlife Service to develop models that anticipate the risk of eagle collisions at a given wind facility, helping to create a framework for wildlife management that can be adapted over time as more data becomes available.

“Being able to look at the potential consequences of one decision versus another and project into the future what they might look like is an amazing tool, and people like Leslie are really the ones that help us do that in a rigorous way,” said Emily Bjerre, a biologist in the service’s national raptor program who has worked with New for nearly a decade.

As research adds to the vast store of human knowledge about animals, there is both more opportunity and more need to use that knowledge to minimize our impact. Whether the population in focus is the bald eagle or the North Atlantic right whale, whose declining population New has helped explain through her modeling, the data stands ready to help inform our actions.

“It’s really important that we make decisions as a society that are decisions rather than defaults,” New said.

In her enthusiasm for statistical ecology and in the education of a new generation of students—some of whom might have once thought, like her, that they didn’t need math—New is working toward that goal. And in an increasingly connected world where changes in our oceans offer a warning for a warming world, it’s never been more important to listen to the data.

“Everything on the planet has value inherently, not just because of what we can learn from it,” New said. “But even if that’s not a view we share, there are absolutely things that are important to know about marine mammals if we as humans are going to survive.”

Read more about Professor New in our research magazine, URSI.