What keeps women from running for public office?

Abby Peabody ’22 and Annie Karreth, associate professor of politics and international relations, discuss the reasons—including financial barriers and cultural and social obstacles—that keep women from running for public office.

Women make up more than half of the population of the United States, and yet only a quarter of women occupy seats in the United States Congress. Some might assume that Americans are still simply hesitant to elect women to positions of power, but recent research has revealed that women are just as likely as men to be voted into office; the problem is, they’re scarcely found on ballots to begin with. So why aren’t more women running for public office?

The reasons are many—from financial barriers to cultural and social obstacles. We’d like to highlight three factors.

First, political scientists have found a measurable gap in political ambition between men and women. Some of this is rooted in cultural norms. From a young age, girls are often implicitly taught to diminish their skills and achievements, while boys are taught to value characteristics like assertiveness, confidence, and self-promotion—traits particularly well-suited to a career in politics. Moreover, according to polls, college-age women and men tend to have differing views on the most effective ways to bring about societal change—either within governing institutions or outside of them. This leads to different career choices, as women opt for jobs in the non-profit or charity sector, while men choose elected office as the best means to promote change.

A second reason why, historically, fewer women have run for office is due to what political scientists call the “role model effect.” In the past, the lack of women in prominent elected positions deterred other women for entering the political arena. When women see other women successfully engaging in politics, it demonstrates a world of possibilities open to female candidates. The successful campaign of a female candidate can be all the evidence needed for a woman to put her name on the ballot as well. With just over a quarter of seats in the 117th Congress and around 30 percent of seats in state legislatures nationwide, female political role models have been hard to come by.

Finally, the financial challenges of running for office can be a serious obstacle to female candidates. With fewer linkages to corporate networks (which many male candidates have access to), women are at a measurable disadvantage when it comes to financing their campaigns. Female candidates are also more likely to cite family obligations and childcare challenges as obstacles to running. Just like any political actor, women will only run for office after taking into consideration its costs and benefits. For women in particular, running for office brings financial, emotional, and family costs and, sometimes, those costs can be prohibitive.

The good news? These three challenges are no longer the obstacles they once were. While there has been a dearth of female role models in American politics in the past, the rise of prominent female leaders—like Vice President Kamala Harris or former United Nations Ambassador Nikki Haley—may inspire a new generation of female political talent that may, simultaneously, narrow the political ambition gap between men and women in this country. Moreover, an expanding network of non-governmental organizations like “Emily’s List”—a political action committee that recruits and supports female Democratic candidates—and innovative technologies like Snapchat’s new “Run for Office” app are helping women overcome the logistical and financial barriers to successful candidacy. As the ubiquitous t-shirt says, the future just might be female.

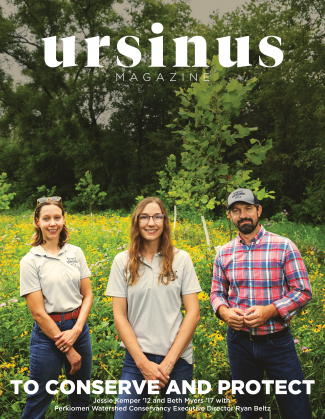

Abby Peabody ’22 is an international relations major who is minoring in Latin American Studies and Peace and Social Justice. For her Summer Fellows project, she researched women in politics and the factors that make them decide to run for office. Annie Karreth is an associate professor of politics and international relations who is the author of The 25 Issues that Shape American Politics: Debates, Differences, and Divisions. She was Peabody’s Summer Fellows faculty mentor.